Shalom Place Community

Shalom Place Community  Shalom Place Discussion Groups

Shalom Place Discussion Groups  Premium Groups

Premium Groups  The Christian Mysteries

The Christian Mysteries  C. The Creation

C. The CreationGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

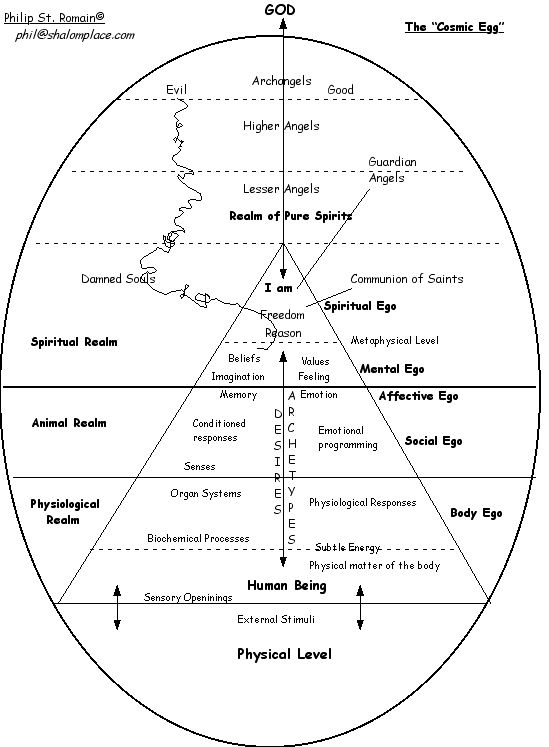

A. General reflections 3 min., 30 sec. Real Audio B. A deeper study. 7 min., 37 sec. Real Audio See also this chapter on evolution by Jim Arraj. - - - General discussion: What are your questions, comments, reflections? What web pages, books, etc. would you recommend? Personal reflection: "I will praise You for I am fearfully, wonderfully made; marvelous are Your works." (Ps. 139: 14) - How do the conferences and the image speak to this sentiment? - How do you understand your relation to other creatures and the universe? | |||

|

From "Evolution": I don't know about you, Phil, but I think this is a great place to start the discussion on Creation. It seems to me that Darwinism absolutely depends on the notion of speciation. If you break that then you break Darwinism for everything but the fine points, such as a bird's beak getting a bit longer, but Darwinism would no longer explain the creation of totally new species of birds. How old is this piece by Jim? Have there been any new scientific developments to refute any of this? How strong is the case really for speciation? Certainly it must have been the lack of evidence that has lead scientists to adopt a view of evolution as acting in fits and starts and not the slow, gradual process as was previously maintained. I guess they too are reacting to the scarcity of good data for gradual change. And if gradual change was a fact of life then just how could a species EVER stay essentially the same over tens of millions of years? That kind of stability makes absolutely no sense in terms of Darwinism. To me it would seem impossible. One gets the strong suspicion that something more is at work here. I've not said the "G" word yet, but I'm sure that'll work it's way into the conversation. | ||||

|

That piece by Jim is just a few months old, and it's pretty much what we learned when I was in grad school in the late 70's. A growing consensus seems to be that most speciation took place during times of environmental duress, with intermediate stages sometimes lasting a relatively short times. After such times of duress, genetic drift slows down, producing subspeciation, which is very well documented. E.g., mice of the genus Peromyscus (I did my Master's thesis on them) have many species in North America. One of the species, P. maniculatus, is very widespread, with many subspecies, some of which look very different. Adjacent subspecies interbreed, but when you interbreed offspring from subspecies that are very far apart, you often get hybrid young. So there is a connected gene pool across the subspecies and that's enough to constitute a species. But imagine that a giant glacier rips down the middle of North America for 30,000 years of so, then recedes. It may well be that when the P. maniculatus populations come together again, they won't even intermingle. Geographic isolation has interrupted the connection in the gene pool to allow for significant diversification to take place. That apparently was the case with P. maniculatus and P. polionotus, which is found only along the southeastern Gulf coast. An interglacial period apparently separated these populations, and now that the water has receded, they just don't get along, even though they're genetically very similar. There are no intermediate stages to be found, here, as it's seldom a matter of a species gradually morphing into another species. I could go on. The dynamics of genetic drift and speciation have been well-established and observed in organisms with short lifespans--especially bacteria, and even, to some extent, in fruit flies. This is a non-issue for 99% of biologists, who recognize the probability of quantum changes during certain environmental stress periods. Evolution has called for some theological adjustments, however. As Jim once told me, St. Thomas would have had no problem with it; his hierarchies of being could still be accounted for if time were considered as part of the process of creation. In my own view, God is no less a Creator for making use of evolutionary processes. It is here that the process theologians (Whitehead, Hartshorne, Teilhard de Chardin, etc.) have done some very creative thinking, much of which is consonant with Christian doctrine, though some apsects are admittedly problemmatic. See http://www.harvardsquarelibrar...ians/hartshorne.html for more info on Hartshorne. Teilhard and Alfred N. Whitehead have references aplenty. | ||||

|

This url http://exit3.i-55.com/~marytanner/panentheism.htm has some discussion that will fold in at some place regarding the creation, evolution and man, also re: Christology. At the appropriate time, I will bring up various points from these musings, but feel free to take an anticipatory look at my perspective. It addresses the challenges of incorporating process theology and process philosophy with long-established and time-honored doctrinal issues and in doing so without going heterodox and tossing out much truth in the process. pax, jb | ||||

|

...and in doing so without going heterodox That's my problem. I'm always on the verge of going heterodox, although I know that kind of thing is strictly frowned upon in some more conservative circles. [That was an attempt at a little levity. Who says God wasn't having a jovial time when he was making the world?] | ||||

|

I'm always on the verge of going heterodox Then I doubt that the Cubs would want you sitting anywhere in the bleachers where you might could snatch a ball from a fielder. | ||||

|

More on good ole Occam: I appreciate all of the prescriptive and descriptive accounts of our research programs in science and theology. For example, at one point, I think Phil Hefner properly critiqued Nancey Murphy in the past re: some aspects of her use of the Lakatosian model. To some extent, I think that: a) Perhaps one reason for the tenacity of worldviews is that they are so comprehensive and so broadly explanatory that they simply can not readily lend themselves to falsification. b) Also, there are those godelian-like constraints to consider for certain issues addressed by holistic accounts. c) Further, not even Occam's Razor can cut to the worldview chase; this is because the law of parsimony requires a choice - not just between two competing explanations but - between two competing explanations that each have explanatory adequacy, such as is not available, for instance, re: pre-Big Bang-isms. d) Finally, even when our methodologies do overlap in their employment of indirect evidence, inductive logic, inference-drawing and such, 1) we've got category errors to avoid by 2) eschewing the conflation of our -ologies and our -isms and 3) being alert to the distinctions between the rational, non-rational, meta-rational and ir-rational. For those who insist on using Occam�s Razor to slice away at worldviews, which is simpler: Hartshorne�s ontological argument using modal logic or the Hawking-Hartle Model using Richard Feynman�s proposal to treat quantum mechanics? pax, jb | ||||

|

- following up on a post I just made on the previous thread "In the beginning . . ." ------- The fact of our existential contingency suggests a Creator of some kind, but how does this affirm the levels of being discussed on this thread? At this point, I will introduce two concepts that I believe have relevance. The first is the idea of entelechy. It is entelechy for the acorn to become an oak tree; although it is not yet one, the acorn possesses the information, intelligence and energetic dynamics to realize its destiny. What, then, of the universe and spiritual consciousness? As the universe has, in fact, produced spiritual consciousness--namely us, and perhaps other planetary races--can we surmise that an entelechy has existed all along for the universe to do precisely this? Such a hypothesis seems more plausible than that of an emergence of human life through strictly accidental occurrences. The various levels of being, then, can be understood as the "creation groaning in one great act of giving birth" (Rm 8: 22). And here we are! Finally, a creature who stands in a position to consciously understand and appreciate the process from whence we have come! Finally, a being who can say "thank you," and who can return the love of the One Who has birthed us through so much patient waiting through the eons. Perhaps, given the lawfulness of this universe, the emergence of the human required all of this--all the galaxies, solar systems, and multitudes of creatures--so that, statistically, the human outcome could be assured. That's very teleological, I realize, and my own suspicion is that there are many more races of conscious, intelligent beings sprung from this abundance. Nevertheless, the levels of being can be understood as necessary and foundational for the emergence of the human and, hence, the fulfillment of the entelechy of the universe. Of course, what I'm leaving out, here, is the next rung on the ladder of being: the Christic! Here we finally see the divine Word through whom the universe was created emerging in the universe itself--the divine realizing itself in its own creation, and creation finally realizing its deepest entelechy--to provide a new dimension of realization for the divine. Here the human level itself is understood as foundational for the divine emergence, with spiritual faith the means for humans to gain access to their deepest, truest destiny in Christ. For more reflection on the Christological entelechy, read about Teilhard de Chardin's notion of Omega Point, click here (and turn the sound off) and here and be glad you didn't have to type that URL. | ||||

|

And to think, in all of this unfolding we are not just idle bystanders; we are co-creators -- as I wrote before: I see our roles as co-creators in influencing the rest of creation (via consciousness, ministry, prayer and stewardship) and urging it on toward its primal destiny such that the omega point yields such a habitation, in nature, as is suitable for the fullest expression of that Incarnational Reality, Who has already taken hold of us, though He was not of human estate. This all tracks Joseph Bracken's ideas of our emergence out of a divine field, a divine matrix -- in a panentheistic, process approach that I think jibes with Jim's ideas, too, re: formal fields. Not sure though. | ||||

|

Below is a cross-posting from philosophyforums in which I considered Creationism --- If we properly distinguish between the enterprises of physics/science, mathematics/metamathematics, formal logic, philosophy/metaphysics and metametaphysics/theology and such, then we can properly avoid the conflations of our -ologies with our -isms, whether the -isms of scientism & materialism or fideism & creationism, etc or the -ologies of scientific cosmology or evolutionary biology, etc Surely, there is sufficient modeling power for reality inhering in both the theistic and nontheistic webs of coherence? Clearly, there are alternate models for reality that are also logically consistent, mathematically harmonious, metaphysically possible, internally coherent, hypothetically consonant, interdisciplinarily consilient and scientifically congruent? Further, if the God-concept of theology is predicated using transcendental analogues for an unknowable and indescribable uncreated nature, Whose causes remain veiled even as the effects are observed, then there are no entities or events in the putative created order that are dispositive of God's nature and such entities and events can only provide analogical knowledge of the Divine Attributes, such knowledge, of course, in principle, being rather meager, even if considered by some as otherwise indispensable. As putative effects of a First Cause, such entities and events, potentialities and actualities, are dispositive of God's existence, comprising both ontological and cosmological arguments that are considered valid by many and even sound by no too few, even if not universally logically coercive or conclusively rationally demonstrable. A God-concept, thus predicated, does not then rise or fall based on the inferences of ID proponents or Big Bang cosmologists or others. If, for example, irreducible complexity was falsifiable or verifiable, it is quite possible that its verification could create problems for atheistic materialism while, at the same time, its falsification would have no bearing on either a thomistic metaphysic or Catholic theism. If the Big Bang finite universe was verified over against other cosmological models that require an infinite universe, it is quite possible that this verification could create problems for a materialist monism, while, at the same time, its falsification would have no bearing on either a thomistic metaphysic or Catholic theism. If the hard problem of consciousness got resolved in favor of an ontologically discontinuous paradigm that verified the noncomputational, nonalgorithmic nature of some human cognitive capacities, it is quite possible that this verification could create problems for eliminative materialist, epiphenomenalist and/or supervenient/emergentistic paradigms while, at the same time, its falsification would have no bearing on either a thomistic metaphysic (especially if informed by process metaphysics or even by a robust understanding of deep and dynamic formal fields) or Catholic theism. Why do these inferential paradigmatic swords seem to slice only in one direction, which is to say as possibly against materialism while not even dispositive of theism? I propose that this answer lies in the notion that, however much gaining their impetus from their respective theologies of nature, Behe's ID inferences, Craig's cosmological inferences and Dembski's cognitive inferences, are essentially metaphysical arguments, while the theistic inference is moreso a metametaphysical argument, which is to say, transcategorical to math, logic, physics and metaphysics. Metametaphysical (theological) inferences (note below), acting axiomatically for the lower degrees of abstraction --- mathematical, logical and metaphysical degrees --- can accomodate many alternate hypotheses for the physical level. In the same way, metaphysical inferences, also acting axiomatically for lower degrees of abstraction --- mathematics and formal logic --- can also accomodate many alternate hypotheses for the physical level. However, a strict materialism or materialist monism, as a metaphysical inference, ends up ipso facto conflating its axioms with those of math and logic, hence, what is necessary and/or sufficient to defeat materialistic inferences is neither necessary nor sufficient to defeat theistic inferences. The above-described degrees of abstraction, however much they may confound or be derided by strict materialists, are not some de novo "wedge strategy" devised by the extreme right; rather, they mirror the godelianesque reality that inheres in human cognitive capacities for goal-setting, intentionality and propositional attitudes, for alternating criticism and conjecture, for verification and falsification, not just of facts but also, of axioms. These degrees of abstraction were integral to Aquinas' medieval synthesis of aristotelianism and Christianity and the resultant metaphysic remains resilient and versatile in modern times, even anticipating ongoing "causal joint" discussions. Now, it may be that this situation may well serve such a wedge strategy, but I am restricting the scope of this musing to the descriptive, not interested in adding to the superabundant prescriptive literature regarding same. However, there is anecdotal and practical experience that lends support to my theoretical speculations. For instance, Craig's version of the Kalam Cosmological Argument, if both valid and sound, would spell trouble, not just for materialism but also, for Mormonism, both relying on an infinite or eternal universe, obviously the former nontheistic, the latter theistic. This is not a new debate but one that raged, even in the 13th Century, between St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas Aquinas, the former claiming that a finite universe was demonstrable only through reason, the latter denying same. Of course, even the early Greeks, such as Democritus, had an infinite universe cosmology. For Aquinas, the world seems to have had a beginning but such was not a necessary condition of creation, the salient point of his cosmological argument being that the world resulted from a free act. His was a proof of theism and not a proof of creatio ex nihilo. Thus the failure of Craig's argument would have no bearing on the many other forumulations of the cosmological proof. Similarly, when it comes to the hard problem of consciousness, there are several paradigms that consider certain human cognitive capacities to be nonalgorithmic/noncomputational and which suggest an ontological discontinuity of sorts without affirming any theism. Some suggest a naturalistic dualism (or dualistic naturalism). Some add consciousness as a primitive (fundamental property of the universe) along side space, time, mass/charge/energy. Others search confidently for yet to be discovered, highly nonlinear, quantum phenomena to explain consciousness. So, on one hand, the falsification of such paradigms as would allow for artificial intelligence supervening on physical states or natural causes like computers would not necessarily lead thinkers like Chalmers, Searle, Ayn Rand or Penrose to theistic inferences. On the other hand, there is the ability in both process metaphysics (like that of Whitehead and Hartshorne and Joe Bracken) and thomism (via a robust understanding of deep and dynamic formal fields, like that of Arraj and consonant with Bohm's implicate order, Sheldrake's morphic resonance and Jung's synchronicity, for instance) to square those paradigms with both supervenience-emergentism and extrinsic telos in an explanation of consciousness. Whatever Behe, Craig and Dembski may be up to regarding their "wedge strategy", I doubt that they are losing much sleep over the possibile success that materialists' counterlogic might have because, it seems to me, metaphysical syllogisms cannot be used against metametaphysical inferences, if the concepts are properly rigorously predicated, sufficiently nuanced and uncontradictory and if the logic is valid. One might argue that certain premises are untrue and that the metametaphysical arguments however valid are nonetheless unsound. At this point the arguments and counter-arguments usually turn to reductio ad absurdum analyses and much confusion ensues as to whether or not certain mathematical, logical and metaphysical possibilities are actually physically possible. Now, it does seem to me that any acquiescence to a materialist's request for a demonstration of causal joints might include an implict category error. At the same time, while one cannot arbitrarily and a priori rule out certain creationist hypotheses, one had better expect to have those subjected to empirical and a posteriori falsification, along with rigorous peer review. One might also expect that s/he will not escape the falling stones when crashing the walls of either religious or scientific tradition, to borrow a metaphor from Gibran. I suspect the ID gang has their eyes open to all of these caveats and, intentionally or unintentionally, their strategy is certainly transparent. In reading this essay by Teed Rockwell of Berekeley, CA, at http://forums.philosophyforums...howthread.php?p=6893 , especially the following excerpt, I could not help but to think of the irony in the similarities between the approaches of these ID proponents and that of Rorty: "If we accept (as I think Rorty does) that the exact divisions between all scientific specialties are decided by social convention rather than by where nature has placed carvable joints, why is there any problem with the fact that the specialized borders of philosophy are drawn vertically (by levels of abstraction) rather than horizontally (by subject matter)? This is basically the point that Haack makes when she says that "giving up the idea that philosophy is distinguished by its a priori character encourages a picture of philosophy as continuous with science. . .but this does not oblige one to deny that there is a difference in degree between science and philosophy" (Haack 1993 p. 188){2}[Haack, S. (1993) Evidence and Inquiry Basil Blackwell Oxford.] If you ask me, this all looks like a big tu quoque argument between -isms that conflate -ologies, which I see as perfectly acceptable as long one does not fool oneself and as long as one practices truth in labeling. pax, jb Note re: metametaphysical (theological) inferences - from Antonio Rosmini's "Knowledge of Essences": "With real things, he has the relationship of cause. We know this because we know the effects of God, as we call this thing unknown to us. It is true that the effects do not reveal the cause itself, which remains veiled, as it were. But it is also true that these effects are so proper to this cause that they are impossible to any other. Consequently, through them, as through a sure sign, we have delineated the cause in such a way that we cannot mistake or confuse it with any other." | ||||

|

When I was an evangelical and back in college I was able to write a paper on how the first cell was made. at the time I was a long day creationist ( or a creationist who beleived the day in genesis 1 was not a literal 24 hour day) and I leaned toward thiestic evolution. I guess the theory that has made the biggest impact to me is the Grand design theory being offered by some major scientists who were once athiestic evolutionists who have come to the conclusion that without a guiding force the theory of evolution would not work. Many of the proponents of this theory are not christian but it is very Christian or religion friendly. I have to admit for me evolution by itself including some of its new manifestations I find wanting and unsatisfying. For me life cannot exist ultimately without a creator and evolution or any science that steps into metaphysical realm oversteps itself. We can study the processes in motion or how species have changed over time(even this requires some guesswork) but beginnings is purely based on theory and conjecture. I guess in a way I am still a creationist and look at Genesis as God's way of telling an ancient people that he is the creator and how things are interconnected. | ||||

|

I guess in a way I am still a creationist and look at Genesis as God's way of telling an ancient people that he is the creator and how things are interconnected. Brjaan, I suppose it would be fair to characterize Genesis as a myth inasmuch as it evokes an appropriate response to Ultimate Reality, God, even though it is not literally true. Wittgenstein's saying that it is not how things are but THAT things are which is the mystical, and Heidegger's question, why is there not rather nothing? , both capture part of the appropriate response that is conveyed in Genesis, which, to me, is that there is a creation and a Creator and that we are creatures. That is my short response: you are right on. I will fashion, below, a longer response, just for giggles. It won't be as clear because of the nuancing required to treat the issue depthfully. Some claim that Creation is, instead, Uncaused Being. While that claim may, on the surface, appear to be no less resonable than the proposition of an Unmoved Mover, we must realize that there is all the difference in the world between the two concepts, Uncaused Being and Unmoved Mover, because the former is being predicated for physical and/or a putative metaphysical reality and the latter of a putative meta-metaphysical reality. Physics and metaphysics deal with how things are, whether material or immaterial or both and other matters related to such things , while meta-metahysics (or natural theology) deals with that things are and other matters related to a Cause that is No - thing . It is certainly true that one does not eliminate the paradox of existence by the introduction of the Creator-concept, that the question of being is still left begging as the mystery of that things are still perdures. However, Antonio Rosmini's statement rings true: Thus the Uncaused Being-concept that includes physical and/or metaphysical reality is delineated and predicated differently from the Unmoved Mover-concept and the Unmoved Mover-concept, apophatically predicated (which means being described wholly in terms of what it is not), should not therefore be mistaken or confused with any other physical or metaphysical concepts. It is true that the mystery of being perdures in either case, whether one is using an Uncaused Being hypothesis or an Unmoved Mover hypothesis. Neither hypothesis is unreasonable but most people find the Unmoved Mover/Creator hypothesis much more compelling, its rational justifications bolstered by so many existential warrants, which is to say, so to speak, by personal experiences of all types. Most people likely don't deal with explicit rational justifications for belief in a Creator, anyway, but rely, rather, on profound intuitions that, if articulated, would correspond precisely to the God-concept of the philosophers and the natural theologians. What we feel intuitively and articulate essentially is that, while a Creator-concept does not do away with the paradox of existence, the idea of a Creator introduces the possibility that, some how this paradox dissolves and, along with it, the paradox of infinity, too. The Creator-concept introduces the idea of a truly transcendent realm, among other things, to account for our experience of the deep paradox of existence by suggesting that we may be comprehended by that which we cannot comprehend, analogous to our everyday experience of hierarchical being (such as in our study of physics and biology and animal behavior and such), where we comprehend realms that cannot, in turn, comprehend our own, which is not to claim, for instance, that a dog does not find the human realm somewhat intelligible even if still incomprehensible. Thus philosophy (metaphysics) and natural theology (meta-metaphysics) seek intelligibility for putative higher realms that remain incomprehensibile to us. Those who propose the Uncaused Being-concept for existence claim that the ontological riddle, why is there something and not rather nothing , is a pseudoriddle and that existence is not a suitable predicate for being (so to speak, does not add new information). They don't draw what is called the ontological distinction , which is the distinction between being, itself, and the act of being . So, at bottom, they are trying to dissolve the paradox of existence by claiming that Heidegger's question is nonsensical and that Wittgenstein's distinction is meaningless. Even if one stipulates that Heidegger and Wittgenstein are wrong (and all of natural theology and metaphysics, too), the paradox of infinity (in this case, re: the infinite regress of causes ) would remain. So, what it comes down to, I suppose, is whether one believes that such paradox is intrinsic to existence (as experienced, for example, via Godel's incompleteness theorems) or whether that paradox must somehow eventually dissolve, dissipating in a Cloud of Unknowing as far as we are concerned but dissipating nonetheless. It is common sense that suggests that all paradox is, at bottom, due to appearances and unreal. It is a queer view, indeed, to suggest that an infinite causal regress is somehow real and just the way things are. Even if the universe is eternal, still the idea of a Creator introduces a fiat to situate, conceivably paradox-free, physical and/or metaphysical causalities in a primal ground and a primal origin (creatio ex nihilo) with ongoing primal support (creatio continua). What it boils down to is our sneaking suspicion that all paradox is due to appearances and that reality, taken as a whole, is paradox free from at least one vantage point. Those who reject the Creator-hypothesis are claiming that paradox is intrinsic to reality, at least where infinite causal regress is concerned, that there is no vantage point that could free reality of paradox. Now, who are the real Mysterians ? pax, jb | ||||

|

Those who propose the Uncaused Being-concept for existence claim that the ontological riddle, why is there something and not rather nothing , is a pseudoriddle and that existence is not a suitable predicate for being (so to speak, does not add new information). They don't draw what is called the ontological distinction , which is the distinction between being, itself, and the act of being . My Thomism is a little rusty, JB. Care to elaborate on the distinction between "being" and "act of being"? | ||||

|

Those who propose the Uncaused Being-concept for existence claim that the ontological riddle, why is there something and not rather nothing , is a pseudoriddle and that existence is not a suitable predicate for being (so to speak, does not add new information). They don't draw what is called the ontological distinction , which is the distinction between being, itself, and the act of being . Recall, first there is a mountain? That is the dualistic recognition of how things are. Next, then there is no mountain? That is the nondualistic recognition of that things are. In Thomism, how things are would correspond to essence and that things are would correspond to esse , which can also be considered the act of being . You can check out this Intro to Metaphysics by Paul Gerard Horrigan , wherein the act of being is discussed throughout but especially in Chapter 7. He also points out Hegel's errors, btw. | ||||

|

Thanks for the further explanation, JB. I thought your first one was rather good and I supposed that I couldn't be the only one to have been tripped up on that point. One gets the feeling that if one could attain the same grasp of these things that you have that one would then have quite a head start on understanding. | ||||

|

| Powered by Social Strata | Page 1 2 |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|